Body lice lay eggs on clothing, feed on human blood, and can transmit disease to humans. People without housing and living in crowded conditions have a higher risk of body lice than others.

Lice are parasitic insects, meaning they need a host to survive. Three types of lice feed on humans: head lice, pubic lice, and body lice. All species of lice are different, but they die without access to human blood.

The effects of lice on humans often involve severe itching and scratching that can lead to skin infections. Lice eventually die without feeding on humans, and treatment involves removing them. This article explains the causes, symptoms, and treatment of body lice.

Body lice live on human clothing. They measure about

These lice can transmit diseases, including:

- relapsing fever

- trench fever

- typhus

They lay about eight eggs, or nits, on the fibers of clothing daily, clustering close to the seams. These may take 6 to 9 days to hatch. They are extremely small and difficult to see with the naked eye.

Body lice can only crawl instead of jumping or flying.

Lice move from person to person

- clothing

- beds

- linens

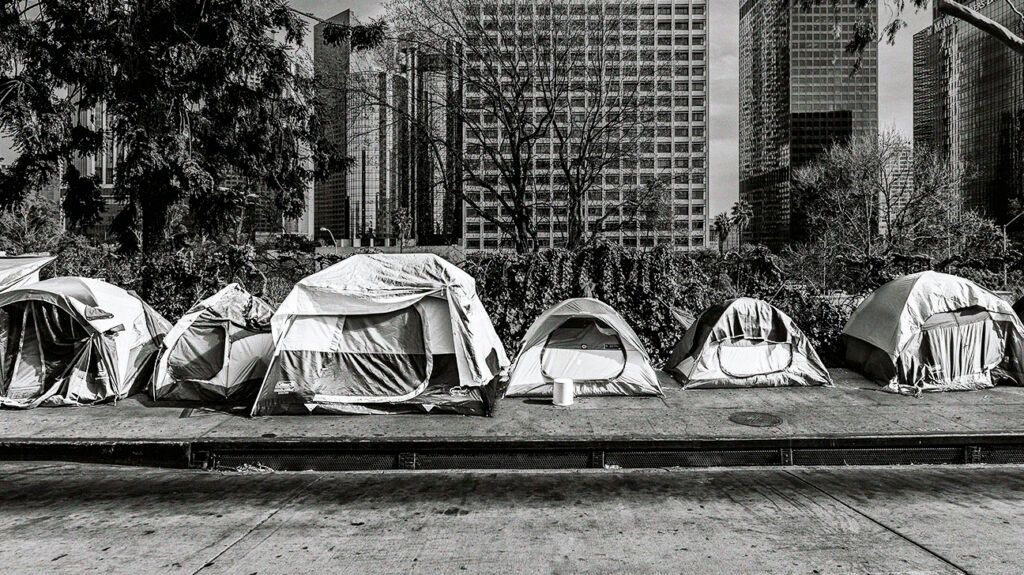

For this reason, body lice are most common in those who do not have access to bathing or laundry facilities, particularly when living in crowded conditions. In the United States and other high income countries, people without housing most often contract body lice.

Risk factors

A French study following 2,288 people in a shelter for homeless individuals between 2000 and 2017 found that

- older adults

- those who stayed in the shelter for longer periods

- those who consumed alcohol frequently

- those who smoked tobacco

- those who were underweight

Other populations at risk of body lice worldwide include:

- refugees

- survivors of war

- survivors of natural disasters

Severe itching is the main symptom of body lice infestation. The itching may be persistent enough to lead to constant scratching and the development of sores. If people experience an allergic reaction to the bites, a rash might develop. Bacterial or fungal infections may develop in these sores.

Long-term body lice infestation can lead to skin discoloration and thickening, often around the groin, upper thighs, and waist.

Adult body lice may be about the

People who believe they may have body lice need to consult a healthcare professional to confirm the diagnosis. According to older information from the National Health Care for the Homeless Council (NHCHC), shelter staff may also be able to assist with diagnosis by taking the following steps:

- asking about itching or other body lice symptoms

- referring any people with body lice symptoms for medical consultation

- wearing disposable gloves and inspecting the clothing and bodies of those who have reported symptoms

The NHCHC suggests that homeless people with body lice should not receive instruction to leave the shelter. Instead, guidance suggests that they should stay an additional night and return with a doctor’s note confirming that they have received evaluation and commenced treatment.

Washing clothing, towels, and bedding that a person with body lice has used at

Treating the body is often not necessary. However, a doctor might prescribe a pediculicide, which is a type of medication that kills lice. People need to follow the exact instructions on the bottle. However, maintaining hygiene and washing personal items at least once every week can also kill lice.

Older information from the NHCHC suggests that people working at homeless shelters should wear disposable aprons or gowns while handling laundry for those who have body lice.

Maintaining hygiene is essential for preventing body lice. Where possible,

- regular bathing

- changing into machine-washed clothes more than once weekly

- dry cleaning non-washable items or sealing them in a plastic bag for 2 weeks and storing them

- avoiding sharing towels, beds, bedding, or clothing with an individual who has a confirmed body lice infestation

- fumigating or dusting with chemical pediculicides to prevent body lice from transmitting certain diseases

Body lice are parasites about the size of sesame seeds that live and lay eggs in clothing, crawling onto the skin to feed.

They mainly transmit among closely condensed populations with little access to hygiene facilities or clean clothes, which often includes people without housing.

Body lice cause itching and may spread diseases, including typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever.

Treatment and prevention involve washing bedding and clothes at a high temperature, maintaining personal hygiene, and avoiding sharing linens and clothes with those who have a confirmed body lice infestation. Some people may also need to use pediculicides.

People who suspect they have a body lice infestation need to speak with a medical professional or shelter staff.